What is NDpae?

NDpae is a life-long disorder caused by alcohol interfering with the development of the foetal brain; this is also known as Foetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD).

NDpae Defined

Neurodevelopmental Disorder is a broad term that describes a number of brain-based conditions arising from a range of diverse causes. If the injury to the foetus is from alcohol, it is referred to as NDpae, which stands for prenatal alcohol exposure. We are using the term NDpae because we feel it is more broadly inclusive of the kinds of effects that alcohol can have on the developing foetus. The other term commonly used to describe these conditions, Foetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) carries too many unhelpful connotations, stigmatizing birth parents and children. We use the term “ND” because it allows individuals to choose whether or not to share how their brain-based condition was acquired.

Prenatal alcohol exposure (pae) can cause a wide range of medical conditions in children. These do not diminish with time, they are life-long.

Put simply, alcohol interferes with the global development of the foetus especially the nervous system. Consequently, functions controlled by specialized regions of the brain can be at risk.

NDpae in a Nutshell

- NDpae is also known as Foetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD)

- NDpae is a neurodevelopmental disorder with effects caused by alcohol

- NDpae is a spectrum of life-long brain-related and general health effects caused by the consumption of alcohol during pregnancy

- It is one of the leading causes of mental health conditions

- Most people with NDpae score higher on IQ tests than they can function in the real world – their Adaptive Functioning is compromised

- NDpae causes serious social and behavioural differences

- Each year, in Ireland, at least 620 babies are born with NDpae

- During Pregnancy, less alcohol is better, NONE IS BEST; there is no known safe limit.

- Alcohol damages more babies than any other drug

- Diagnostic terms which sit under the same umbrella as NDpae include:

- Foetal Alcohol Syndrome (FAS)

- Partial Foetal Alcohol Syndrome (PFAS)

- Alcohol Related Neurodevelopmental Disorder (ARND)

- Neurobehavioral Disorder Associated with Prenatal Alcohol Exposure (ND-PAE)

- Alcohol-Related Birth Defects (ARBD)

- Many children with NDpae also have diagnoses for other conditions such as Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD), and Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD).

Living with NDpae

NDpae Effects

Longstanding research shows that people with this condition are likely to face serious difficulties in their journey through life if they have not had the correct support services:

• Orderly, organised and sequential

• Many opportunities for links and interconnections

• Inconsistent growth, disorganised, gaps and clusters • Clusters can appear as areas of strength. Eg. in art, music, etc. These may contribute to overall spiky developmental profiles

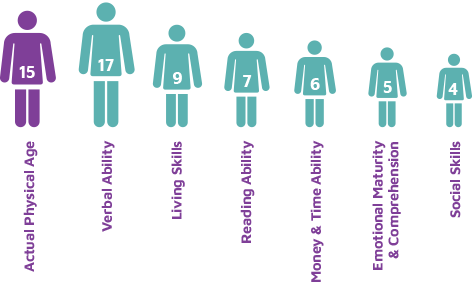

Uneven Developmental Profiles

These diagrams illustrates how people with NDpae present with uneven development. Every person will be different but this is a typical profile.

Things Young People with NDpae Say...

- “I learn best when you show me how rather than tell me.”

- “It’s like my brain wants me to see everything in the room and hear every sound, all at once.”

- “I probably won’t hear what the teacher is saying because I’m hearing someone tap their pencil or people in the corridor or a dog outside or even the heater.”

- “I can understand something one day and not, the next. It can come back another day. It’s crazy for everyone, especially me and very frustrating.”

- “My brain is wired differently so things can just slip in and out of it easily.”

- “I have no answers why I do what I do and I can get very impatient but if you ask me something, I’ll make my best guess.”

- “If my schedule gets mixed up, I just shut down. My brain freezes.”

Things Their Parents Say...

- One of our first clues that there was something unusual going on was when we realized she simply didn’t learn from experience, that “consequences” didn’t work.

- The explosive tantrums – some people call them Blow-ups or Melt-downs – are really hard to take. I find it difficult to stay thinking and not reacting, remembering that this is a damaged brain reacting to something it can’t deal with.

- “Listening to music really helps him. These days, after listening to his music, he can talk about what is wrong or what happened.”

- “She has great long term memory but often can’t remember recent things. It makes it hard to help with homework or new things she’s learned at home.”

- “I worry about him being alone – people often don’t want to play with him.”

- “She loves being creative but it sometimes drives me crazy when she makes such a mess.”

- “Until we learned we weren’t the only family dealing with this, we were in a very lonely place. Often we felt hopeless.”

- “Some of the stories she can tell are brilliant. I’d nearly believe them.”

- “I’ve recently heard that research is showing brain resiliency means some recovery is possible.”

- “We see the round the clock picture. Everyone outside the home sees the best-out takes and can’t understand the challenges to a “normal” life.”

- My most useful mantra is “Can’t, not Won’t.”

Things Parents Say...

I have to acknowledge the role played by a Social Worker from CAMHS and by a Youth Worker from Foroige in the team we have built around our child. That she is (mostly) doing so well, physically and mentally and is looking forward to engaging with the Leaving Cert Applied programme is in no small part down to these two amazing women. That we, as parents, have had them as a sounding board, as interpreters of confusing behaviours and as sources of reassurance, has been vital.

The parenting can be really hard:

- Feeling like I’m in an abusive relationship, often walking on eggshells

- Wondering will it ever get better, feeling helplessness

- Worried about the effect on other children in the family

- Wondering will she come home tonight?

- Fearful of pregnancy due to her vulnerability

I’ve found many things to appreciate about raising our child with FASD.

- She is very lovable and now she is growing up she craves a love ‘just for her’

- She is very protective of friends and family and always supports the underdog

- She is confident and happy most of the time

- I try to look for the positive in things, remembering that I’ve done my best

- I’m often astonished at how far she and we have come

When she gaily talks about having ‘a few cans’ with her friends, and I point out the ‘toxic’ in inTOXICated, knowing how her brain has been programmed for addiction.

What I have christened ‘Fugitive Memory’ is difficult. We can spend ages discussing some course of action and coming to an agreement, only the next day to find it has disappeared from her consciousness. Of course, it it may reappear days or even weeks later, usually prefaced by her saying “I’ve always…”

The psychiatrist at CAMHS really seemed to understand FASD. He reviewed her medications, adjusted them for how she has grown and added another tablet. Her behaviour has stabilised a good bit and, thankfully, she is eating much better.

There is light at the end of the tunnel! Our daughter is now 29 and is managing so much of her life better than we might have imagined when she was younger. In her first annual performance review at work, she ended the interview by standing up and saying to her boss, “are we done here yet, I’m 20 minutes late for my shift’. In time things do improve

Our children need huge advocacy. It sometimes feels overwhelming, alongside the intensive parenting they need.

I’ve found it useful to set six-monthly timeframes with hoped-for goals. It’s surprising, and gratifying, looking back, to see how many of these have been achieved.

Basic stuff but it works for us!

Our child only presented with really difficult behavioural problems when puberty started.

Being a parent to a child with FASD can be a very lonely experience.

The prospect of my child ‘ageing out’ of CAHMS and needing to rely on adult psych services is scary.

Trying to get services is a joke and difficult behaviours get more intense as the child gets older.